C. Carey Cloud » Articles » Putting Brown County On Canvas

Putting Brown County On Canvas

with John R. Thomson

The Chicago Tribune, October 19, 1975

"For more than a quarter of a century, the artistry of C. Carey Cloud was given away inside boxes of Cracker Jack. Now, at 75, he prowls the farming country around his Indiana home, recording weathered wood with so much realism you can almost feel the splinters."

When fire destroyed the old Brown County Art Gallery in Nashville, Ind., there was some concern about whether "Aunt Molly" had survived. But C. Carey Cloud was able to assure everyone that "Aunt Molly" was all right, having been on loan to Indiana University in Bloomington at the time of the fire. "Aunt Molly" is one of the last broad-stroke oil paintings done by Cloud before he began to paint weathered old barns and farm buildings, abandoned plows and agricultural equipment, and other rural scenes in such detail that the growing number of Cloud fans refuse to rate him below Andrew Wyeth or anybody else when it comes to realism in art.

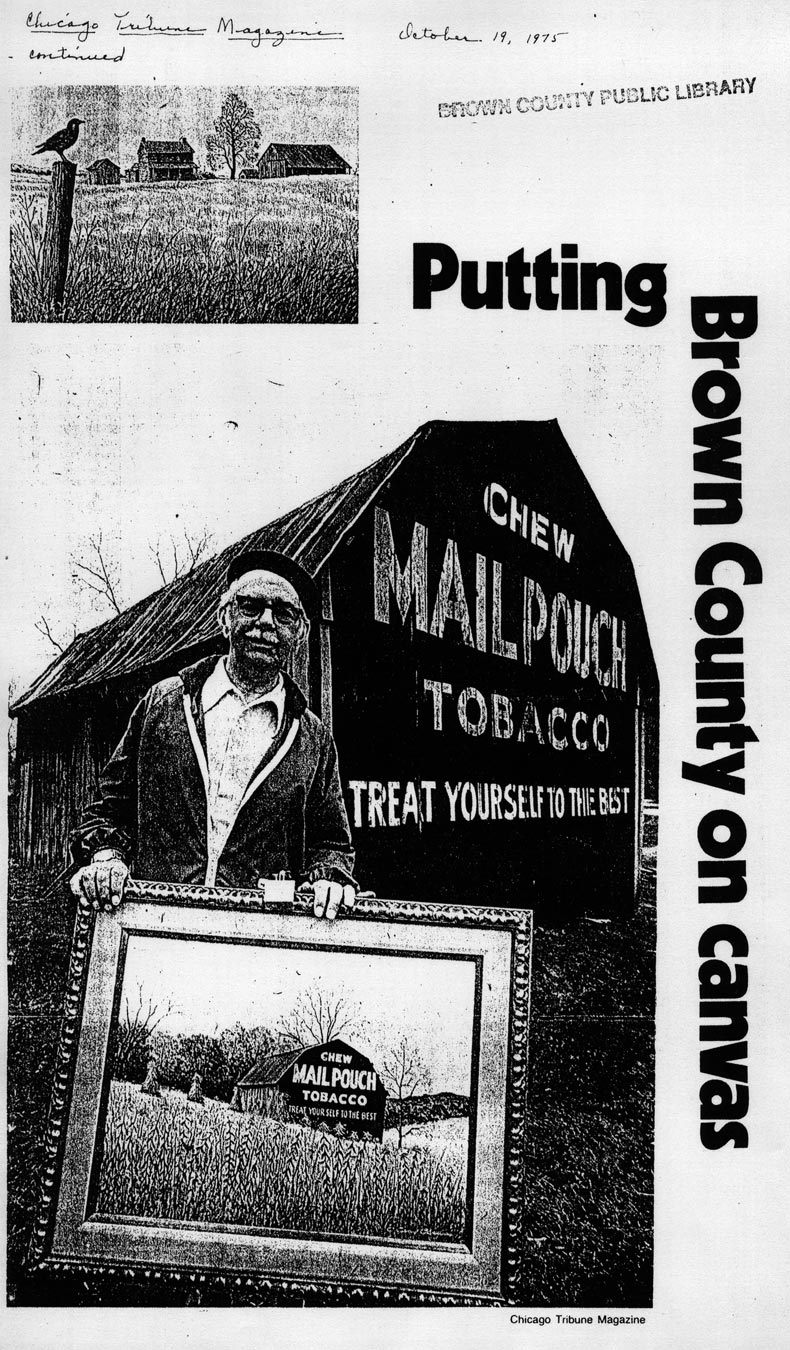

Of course, not everybody shares Cloud's enthusiasm for weathered old-time things. The first "Realism in Depth" painting he submitted to the Brown County Art Gallery was one of a weathered old barn that still stands, altho it has since been remodeled, on the highway between Nashville and Bloomington. On the side of the barn was a "Chew Mail Pouch — Treat Yourself to the Best" advertisement. Cloud reproduced it in detail.

"They-said no one would ever buy that and suggested I paint out the Mail Pouch ad, but I said, 'No, that's what it's all about,' " said Cloud." They also objected to the $695 price tag and suggested I scale it down to a price comparable to the rest of the art, say a top of $200 or so. I said, 'Why, I'm retired. I can't afford to work for 35 cents an hour."

To the amazement of gallery officials, the painting of that old barn was quickly purchased by a doctor from Auburn, Ind. He took it home and looked at it, then drove back to Nashville and bought three more of Cloud's paintings as an investment, saying, "I might as well get them now, before the price goes up."

A few years ago, while spending his first winter at Bradenton, Fla., Cloud submitted a painting for an exhibit in Belleair. He hung "The Sentry," which showed a crow on a weathered fence post.

"A Clearwater critic — he took it for a hawk, incidentally — lambasted it as 'an incident in time' that was not worthy of being called art," Cloud recalled. "When it got an honorable mention, the critic wrote that he couldn't decide what there was about Cloud's work that so enamored the judges unless it was the glazing."

Cloud's wife, Vera, who died in 1971, had a great sense of humor; she laughed and laughed about that critic until C. Carey laughed, too. The review came to the attention of a St. Petersburg newspaperman who recalled that the artist had designed and produced the prizes that went into Cracker Jack packages, and he wrote a story that made people on Florida's West Coast aware that C. Carey Cloud was living in their midst.

Cloud, a pixieish fellow with eyes that twinkle in a face set off by white hair and a trim white mustache, has been laughing — sometimes at his own expense for 75 years, the last 27 of them spent chiefly in Brown-County, which a lot of people think is the scenic capital of Indiana and a lot of Hoosiers think is the scenic capital of the world.

When he finished all the grades in the one-room school near Warren, Ind., he said goodby forever to the plow he often walked behind on the farm and went off to Marion to work in a shoe factory. His job was putting soles on shoes.

"I was left-handed, but I turned out to be ambidextrous on that job, and I broke the tedium with a little act that rather amazed as well as amused the other workers," Cloud said. "The word got around, and three executives of the plant showed up. I gave them my best, and after they went away a time-study man came around. After he got thru I was placed on piece work and my income dropped from $18 to $8 a week. I learned it doesn't always pay to smart off."

World War I came along and the armies of the Western world were grinding up steel in tanks and guns and shells on the battlefields of France, so Cloud left the shoe factory for a job in a Cleveland steel mill. There he also enrolled in a $25 correspondence course, financed on the time-payment plan, at the Landon Correspondence Art School in downtown Cleveland.

Art was not exactly new to Cloud. He had been drawing and sketching thru all the years he spent in that one-room school. After a few correspondence lessons, he wrote the school, criticizing its lessons.

"They called me in and hired me. The Cleveland Press was right next door, and I hung out there most of my spare time," Cloud recalled. "One day the art director at the Press informed me that If I was going to loaf there so much I might as well go to work, and I did."

While working for the newspaper, he began free-lancing for Blue Book and Triple X magazines. By the time he was 20, he was doing so much work for them he decided to move to Chicago, where the magazines were located.

"When I got to Chicago, Triple X went out of business and Blue Book moved its office to New York. I was left high and dry, and I had a wife and daughter to support," he said.

Poring over the want ads in Chicago newspapers, Cloud found that the Baumgart Calendar Co. needed an art director. He applied for the job, asked for $75 a week, and encountered a good deal of skepticism.

"I got the job when I told them, 'Try me, and if you feel I'm not doing you any good, fire me. And if I feel I'm not doing you any good, I'll quit,' " he said. A year and half later, when the company moved to South Bend, Cloud was invited to come along. He elected to remain in Chicago, where he did everything he could to make a dollar, even greeting cards. By 1928, with a son added to the family,- he had his own studio on Wabash Avenue north of the river. It was the first of two studios within a few blocks on Wabash he was to occupy for the next 20 years.

The stock-market crash in the fall of 1929 and the Depression that followed were tough for many people, and few had it tougher than artists. Cloud was one of many who sold his pictures on Michigan Avenue and in Grant Park to any passerby who had a buck or two in his pocket.

He survived, possibly because he had an alert, inquiring mind that generally was tuned to what people might buy. He originated the pop-up book in the 1930s and illustrated 20 of them. The kids loved them. He thought up the book for the Orphan Annie radio program, which you could get by sending 10 cents to Ovaltine, the sponsor.

He also developed the Superman game for the radio program. At the height Of the Superman craze, Cloud found himself in a taxicab with an ad-agency representative discussing the show and the game. At their destination, the cabdriver jumped out, opened the door, took Cloud's hand, and shook it enthusiastically. "I've just got to tell my kids I shook hands with Superman," he said. Cloud still wonders how anyone could think he looked like Superman.

Cloud also designed the four-piece set of plastic trivets that could be obtained for 30 cents and a coupon from Post's Bran Flakes. He still has a set in his Brown County studio.

Possibly it was the small size of the things Cloud dealt with that brought him to the attention of the Cracker Jack Co. in 1937. In any case, Paul Howey of Cracker Jack's purchasing department contacted him. The importer who supplied the prizes was giving it up. How would Cloud like to design and supply the prizes?

"I don't think much of the whole idea of those cheap little things," replied Cloud. "You can't make any money at that."

"Well, he's driving a Cadillac, and I notice - you're driving a beaten-up old Ford," Howey said.

Cloud went back to his drawing board and started designing small prizes. He had dies and molds made and subcontracted production. Cracker Jack paid him on a royalty basis. The first order was for two million prizes. Later orders ran as high as 14 million. "Where have I been all my life?" Cloud asked himself.

For 27 years, Cloud designed, and produced, thru subcontractors, hundreds of millions of prizes. Anyone who's old enough will surely remember the "goofy coins" that came in Cracker Jack boxes during World War II. It was impossible to get tin, but Cloud managed to get scrap lids from a manufacturer of glass jars; the lids turned up in Cracker Jack boxes as "queer quarters," "goofy dimes," "nutty nickels," and as good-luck pieces with the stamp of a horseshoe or four-leaf clover.

When plastic came in after the war, up to 40 million of a single prize design were supplied to Cracker Jack. Only one of the hundreds of prizes he designed for the company was a failure. It was a sea captain with a pipe in his mouth, which was discontinued as a prize after a consumer complained that it looked like Joseph Stalin.

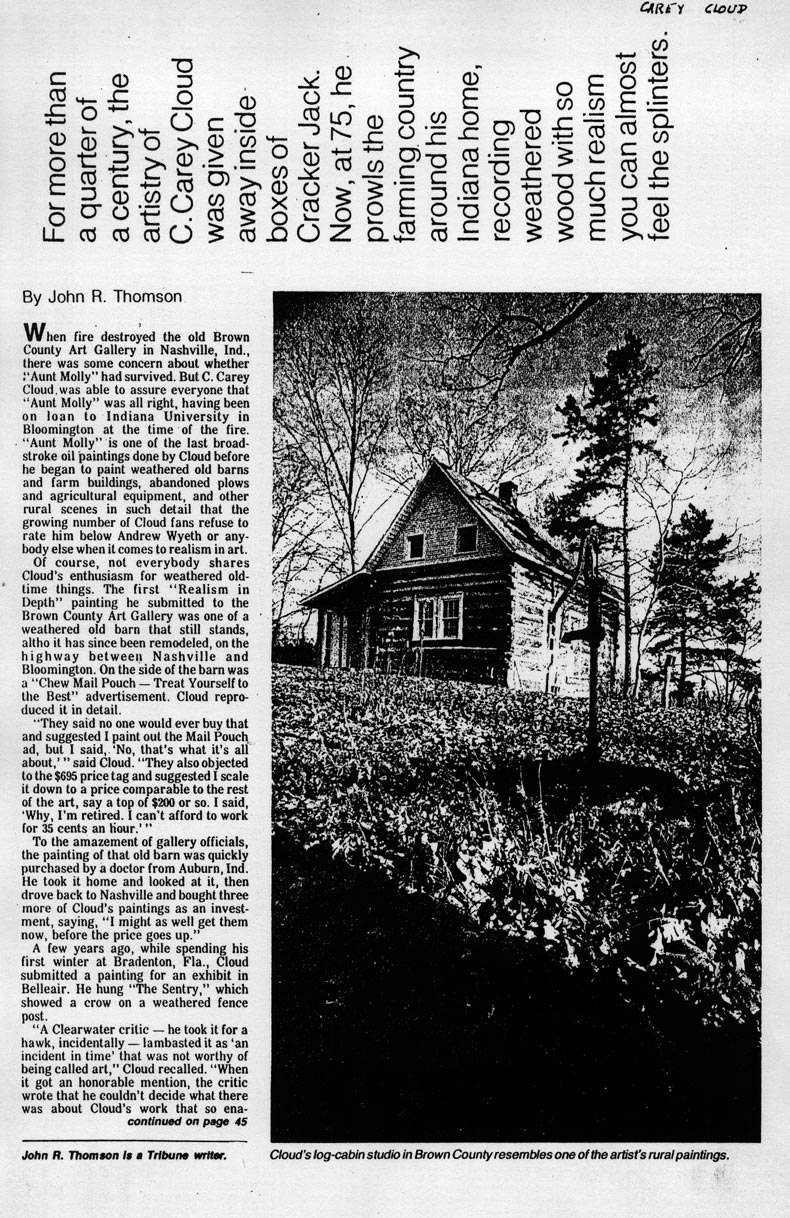

Cloud moved his operations to Brown County in 1948. His studio building at Wabash and Ohio had been sold. He bought the hillside home of a deceased artist, Will Vauter, and 200 acres on the hill just south of Nashville. He and Cracker Jack called it quits in 1964, when the company decided all ideas should originate from its advertising agency. It was a friendly parting because Cloud wanted to try his hand at serious art. He had spent 27 years in comfortable and prosperous obscurity, designing and producing millions of small things. But he'd done his bit for the children of America. He estimated that if each of his Cracker Jack prizes gave at least one child five minutes of play time, he had provided children several million hours of fun.

Cloud then tried "just about every school of painting, every 'istic' and every 'ism' in existence." he said, and he has examples around his home and his nearby log-cabin studio to prove it. He thought he never quite caught the boat.

"I finally asked myself, 'Heck, why am I doing this when I'm trained in detail?'" He decided

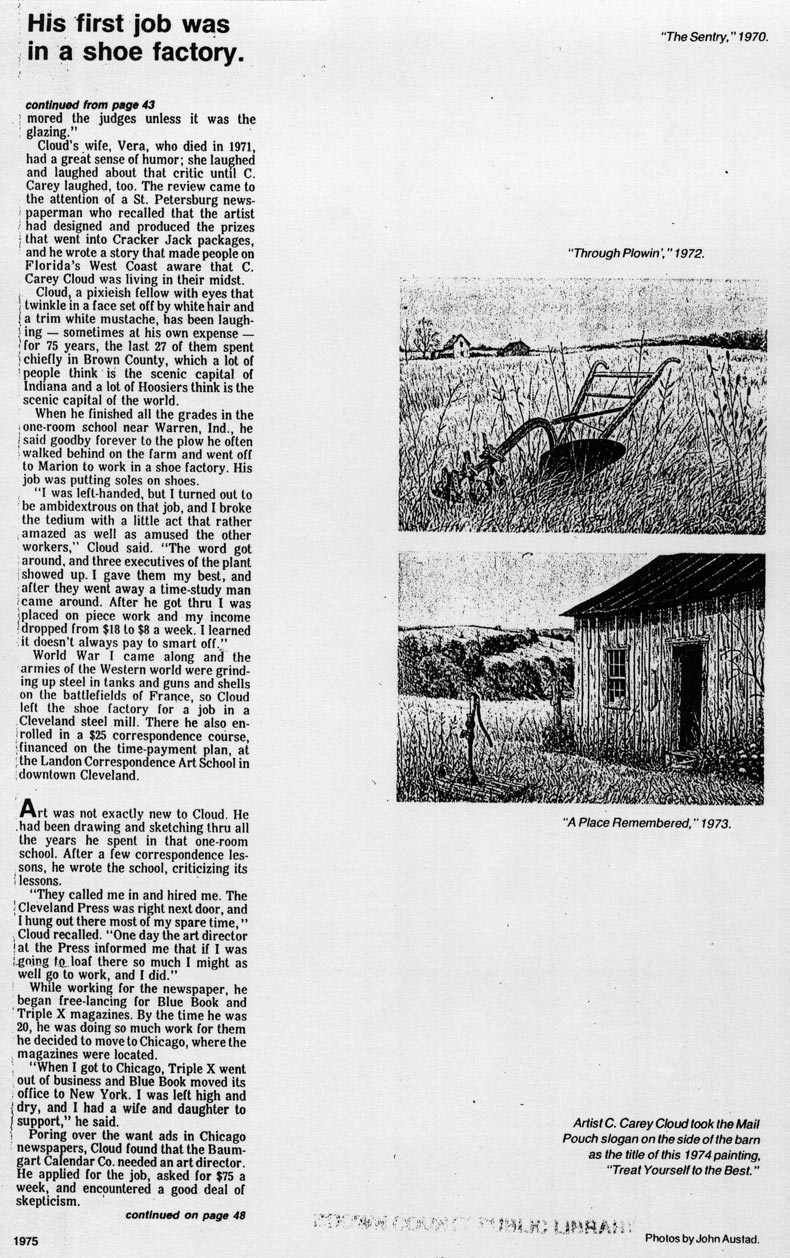

to return to realistic detail and forget design and vivid colors. People who buy paintings, he had discovered, don't like much green in them. That's why he paints weeds and flowers and trees in the color of late summer and fall, buildings and farm

equipment that look like they have long since been abandoned, and wood that seems to have weathered since the beginning of time.

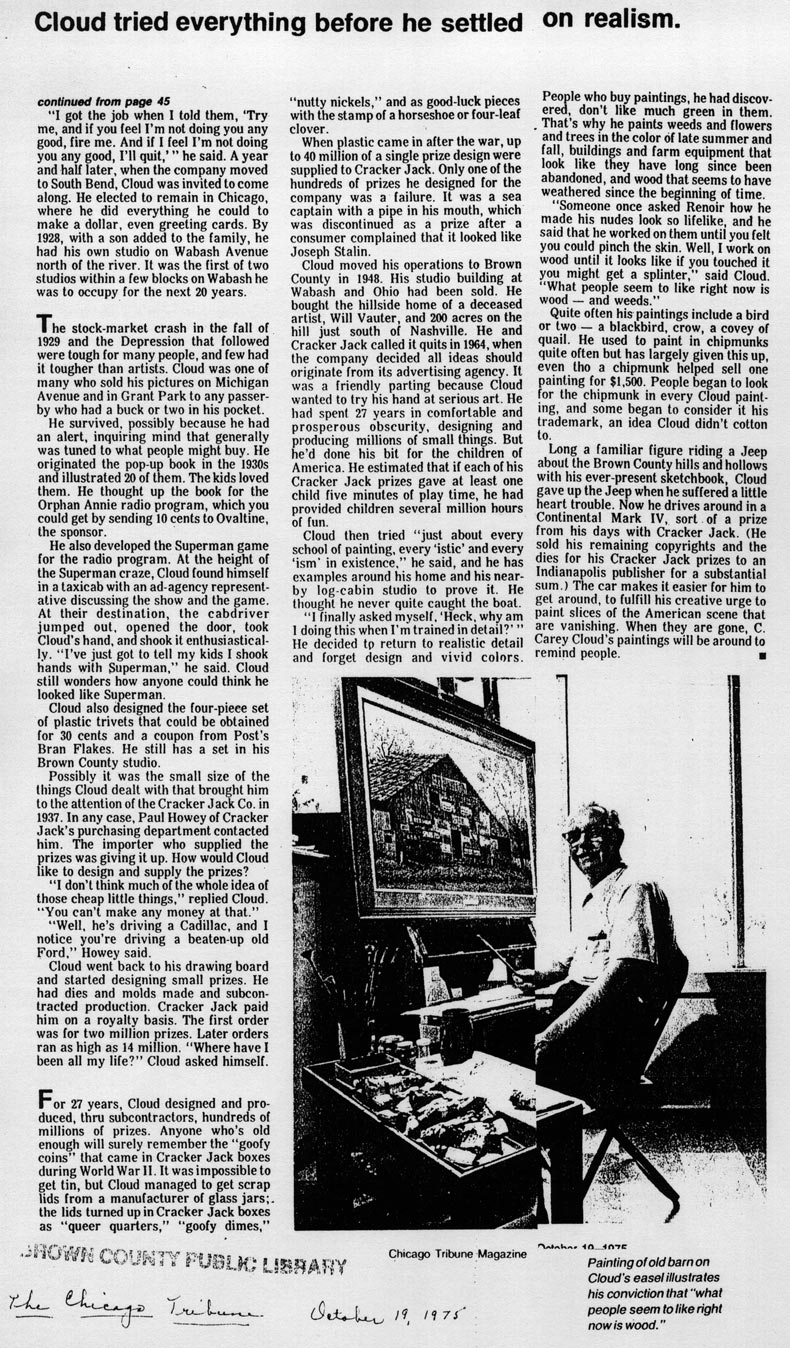

"Someone once asked Renoir how he made his nudes look so lifelike, and he said that he, worked on them until you felt you could pinch the skin. Well, I work on wood until it looks like if you touched it you might get a splinter," said Cloud. "What people seem to like right now is wood and weeds."

Quite often his paintings include a bird or two — a blackbird, crow, a covey of quail. He used to paint in chipmunks quite often but has largely given this up, even tho a chipmunk helped sell one painting for $1,500. People began to look for the chipmunk in every Cloud painting, and some began to consider it his trademark, an idea Cloud didn't cotton to.

Long a familiar figure riding a Jeep about the Brown County hills and hollows with his ever-present sketchbook, Cloud gave up the Jeep when he suffered a little heart trouble. Now he drives around in a Continental Mark IV, sort of a prize from his days with Cracker Jack. (He sold. his remaining copyrights and the dies (or his Cracker Jack prizes to an Indianapolis publisher for a substantial sum.) The car makes it easier for him to get around, to fulfill his creative urge to paint slices of the American scene that are vanishing. When they are gone, C. Carey Cloud's paintings will be around to remind people.